In defiance of the U.S. State Department’s order “NOT VALID FOR SPAIN” stamped on passports, African Americans and their white comrades had to enter Spain illegally. They sailed to France pretending to be tourists and then crossed the border into Spain. After France closed the border to Spain in 1937, however, volunteers could reach Spain only by climbing the Pyrenees Mountains at night.

In Spain, the African American volunteers found life sharply different from what they had left in the United States. When the Lincolns marched, recalled Marion Noble, a white Detroit volunteer, “Spanish women showered the Black men with smiles and flowers.” “I never felt more like a man than in Spain,” reported Luchelle McDaniels. Years later Tom Page told James Yates:

“I remember how sometimes a whole town would turn out when they heard there was a Black man around. Spain was the firstplace that I ever felt like a free man. If someone didn’t like you, they told you to your face. It had nothing to do with the color of your skin.”

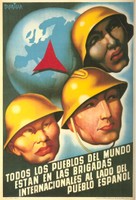

Recruits from the United States were assigned to the English-speaking Fifteenth Brigade that also included British, Canadian, and Irish units, and Spanish-speaking Latin Americans. Linking Spain’s struggle to their own history, U.S. volunteers called their units the Lincoln and Washington battalions and named the artillery and machine-gun companies after abolitionist Frederick Douglass and anti-slavery martyr John Brown.

From infantry privates to officers, the Lincoln Brigade was the first fully integrated U.S. army. Moreover, Communists in leadership positions, such as Steve Nelson, resolved that African Americans would have an opportunity to prove their capacities and leadership abilities. College student Oscar Hunter became the Political Commissar of Hospitals. “How long do you think it might take me to get up to such a position in the United States?” he asked a Black U.S. journalist who answered “not in the next one hundred years.” “I can rise according to my worth, not my color,” noted Oliver Law.

In the unit’s first battle at Pingarr Hill in the Jarama Valley the fledgling Lincoln Brigade faced a baptism of fire without air cover or artillery support. Here Alonzo Watson was the first African American killed in Spain. But 23-year old machine-gunner Walter Garland was twice wounded, commended for bravery and was promoted to lieutenant together with Oliver Law.

Other African Americans also demonstrated raw courage and unusual battlefield skills. Fellow soldiers described Doug Roach as a man with “infectious enthusiasm” who “could carry a heavy machine gun over the hills of Brunete when others were too exhausted to walk.” Luchelle McDaniels, or “El Fantastico,” could hurl grenades long distances with either hand. Lt. Walter Garland trained Milton Wolff, the last Lincoln Brigade commander, who recalled:

“Whatever I learned about the Maxim machine gun he taught me. But more important . . . he instilled in me the conviction that we could go out there and take on the whole bloody professional fascist armies and kick the shit out of ’em.”

Spain had a strong impact on African American volunteers. Salaria Kea discovered “divisions of race, creed and nationality lost significance when they met a united effort to make Spain the tomb of Fascism… I saw my fate, the fate of the Negro race, was inseparably tied up with their fate…” Of the many tragedies she “shared with the Spanish people,” Salaria Kea remembered most vividly the fascist bombings of children’s colonies near Barcelona and an attack on her field hospital:

“I heard screams coming from every direction. I saw people I had never seen before; many moving dirt and shovels, others were using their hands. Some were running with pieces of bodies in their arms. I was in shock. . . . Many of the patients had been killed. Newly wounded patients were being brought in. We began to work on them. Soon we ran out of sterile supplies.”

In March 1938 a hospital bombing left Kea buried for hours. “I was dug out from under six feet of rocks, shells and earth. The resulting [back] injury left me unfit for further hospital service. I was furloughed home.” In the U.S. Kea “traveled through the country to secure medical supplies and food so desperately needed by the people in Spain. This I did until Spain fell to Franco.”

Other African Americans were deeply moved by their experiences. Pat Battle, a quiet medical student at Howard University, told James Yates about the fascist destruction he had seen in Madrid of schools, libraries and educational institutions. He concluded: “The fascists tear down that which it has taken people years to build.”

Oliver Law stood out in Spain for his soldierly background and military bearing. Early in 1937 (the year General Colin Powell was born) Law’s prowess earned him many battlefield promotions. After he was put in charge of his machine-gun company, Lincoln Brigade commander Marty Hourihan recommended Law for officers’ school, and he was headed for leadership.

When the position of Lincoln Brigade Commander became available, Captain Law was chosen. Steve Nelson, who had worked with Law in Chicago and served on the committee of three that picked him, stated “he had the most experience and was best suited for the job.” He was, Nelson emphasized, “the most acquainted with military procedures on the staff at the moment … he was well liked by his men … When soldiers were asked who might become an officer — ours was a very democratic army — his name always came up. It was spoken of him that he was calm under fire, dignified, respectful of his men and always given to thoughtful consideration of initiatives and military missions.”

Law’s friends in the Brigade included his two white runners, Jerry Weinberg, and Harry Fisher, both from New York City. Fisher has provided vivid recollections of Law as Brigade commander. As Law led his men at Brunete in July 1937, Fisher has written, “What I remember is the great joy on Oliver Law’s face as he saw the fascists running. After a while, with the men exhausted and far in front of the tanks, Law feared that we would fall into a trap, and ordered the men to slow down.”

Subsequently, Law took command of the Brunete offensive and was killed while leading an attack against the fascist lines on “Mosquito Ridge.”

Meanwhile on the U.S. home front the African American community gave full support to the Lincoln brigade’s anti-fascist commitment. Wartime opinion polls found that two-thirds of the American public supported the Republic, although most citizens also feared that direct U.S. intervention would endanger world peace. Committees to Support Spanish Democracy formed in Harlem, and national figures such as Lena Horne, W.C. Handy, and Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. played prominent roles in fund-raising efforts.

Famous African Americans toured the war zone. Langston Hughes’ dispatches from the trenches, his revolutionary poetry, and his speeches reflected a growing commitment to what he and others saw as the determination of the world’s common people to achieve liberation, self-determination and democracy. In Spain Langston Hughes cultivated a friendship with the poet Edwin Rolfe, editor of the Volunteer for Liberty. At a meeting in London to raise funds for the Spanish republic, actor and singer Paul Robeson announced his support of the cause in Spain. An artist, he said, “must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery.” Robeson and his wife Eslanda subsequently visited Spain and toured the front to sing for the antifascist troops.

Despite the efforts of the Spanish people and of the International volunteers, the Republic fell to Franco’s forces in March 1939. As Ernest Hemingway began to work on his epic about Spain, For Whom The Bell Tolls, he paused to write an elegy for the American dead.