Biography

Fishman, Moses (Moe), b. September 28, 1915, NY; Jewish; Single; Truck Driver and Laundry worker, YCL (CP) 1934 and Spanish CP; Received Passport# 383528 on April 2, 1937, which listed his address as 2909 Broadway, Long Island City, Astoria, Long Island, New York, and NYC; Sailed April 7, 1937, aboard the Lafayette; Arrived in Spain on April 29, 1937; Served with the XV BDE, Washington BN, Co. 1, Section 3, Runner; WIA July 5, 1937, Brunete; Various hospitals for the next year and worked as a Driver in rear areas until repatriated; Returned to the US on July 20, 1938, aboard the Champlain; WWII Merchant Marine; d. August 6, 2007, NYC.Sources: Sail; Scope of Soviet Activity; Cadre; Washington; RGASPI; ALBA 224 Moe Fishman Papers; L-W Tree Ancestry; Douglas Martin, “Moe Fishman Dies at 92” New York Times, August 30, 2007; (obituary) Peter Carroll, “Moses ‘Moe’ Fishman, 1915-2007,” The Volunteer, Volume 24, No. 3, September 2007, pp. 21-22. Code A

Obituary: “Moses ‘Moe’ Fishman, 1915-2007,” Born in New York on September 28, 1915, Moses Fishman had left school during the Depression and became a laundry worker and truck driver. He participated in unionizing with his fellow workers and found a commitment to social justice issues as a member of the Young Communist League. When the Spanish war began, he volunteered to fight but was rejected for lack of military experience. However, his skill as a truck driver was needed and a second application for service was "accepted” with the proviso that he recruited ten other volunteers. Fishman quickly found the men, though none actually showed up. The recruiters took him anyway. He arrived in Spain in April 1937 and was shot in his left leg during his first action. During his lengthy recuperation from war injuries, Fishman stayed in touch with New York humanitarian aid organizations providing assistance for the civilian refugees of the Spanish Civil War. He eventually worked in the warehouse of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, while studying to become a licensed radio operator. When the United States entered World War II, Fishman's skills enabled him to serve in the Merchant Marines. After his second war, Fishman continued to work with the refugee aid committee, even after it was targeted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities for alleged subversive activities in 1946. Indeed, it was Fishman's proximity to that case that changed his life when HUAC set its sights on the VALB. President Harry Truman's Attorney General listed the group as a subversive organization in 1947 as part of the postwar anti-Communist crusade. When Congress passed the McCarran Act in 1950, obliging all designated subversive organizations to register with the federal government and creating heavy penalties for leaders who refused to cooperate, the entire executive committee of the VALB resigned in 1950. In its place, two Lincoln veterans stepped forward: Milton Wolff became the National Commander; Moe Fishman became the Executive Secretary/Treasurer and served the organization in an executive capacity for the rest of his life. The seemingly indestructible Moe Fishman, the public face of the Americas' Spanish Civil War Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) for more than half a century, died of pancreatic cancer on August 6, 2007, in New York. He was 92. - Peter Carroll, The Volunteer, Volume 24, No. 3, September 2007, pp. 21-22.

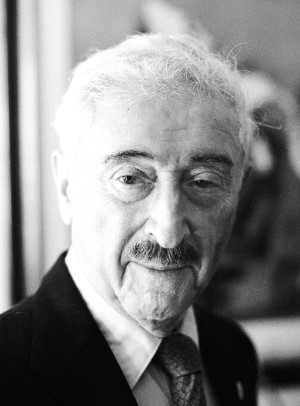

Obituary: Moses “Moe” Fishman (1915-2007) The seemingly indestructible Moe Fishman, the public face of America’s Spanish Civil War Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) for more than half a century, died of pancreatic cancer on August 6, 2007, in New York. He was 92. During the past year, Fishman represented the veterans in public events around the country and in Spain commemorating the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of a war that pitted rebellious generals led by General Francisco Franco and backed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy against the legally elected Spanish Republic. Fishman was one of 2,800 U.S. volunteers who formed part of the International Brigades, organized by the Communist International in 1936 to stop fascist aggression. As a foot soldier in the George Washington battalion, he was wounded during the battle of Brunete, near Villanueva de la Canada in July 1937 and spent a year in convalescence in Spain before returning to his home in New York. He then spent another two years in hospitals as doctors fused bones in his injured leg, leaving him with a lifelong limp. Born in New York on September 28, 1915, Fishman had left school during the Depression and became a laundry worker and truck driver. He participated in unionizing his fellow workers and found a commitment to social justice issues as a member of the Young Communist League. When the Spanish war began, he volunteered to fight but was rejected for lack of military experience. However, his skill as a truck driver was needed and a second application for service was accepted—with the proviso that he recruit ten other volunteers. Fishman quickly found the men, though none actually showed up. The recruiters took him anyway. He arrived in Spain in April 1937 and was shot in his left leg during his first action. During his lengthy recuperation from war injuries, Fishman stayed in touch with New York humanitarian aid organizations providing assistance for the civilian refugees of the Spanish Civil War. He eventually worked in the warehouse of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, while studying to become a licensed radio operator. When the United States entered World War II, Fishman’s skills enabled him to serve in the Merchant Marines. After his second war, Fishman continued to work with the refugee aid committee, even after it was targeted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities for alleged subversive activities in 1946. Indeed, it was Fishman’s proximity to that case that changed his life when HUAC set its sights on the VALB and President Harry Truman’s Attorney General listed the group as a subversive organization in 1947 as part of the postwar anti-Communist crusade. When Congress passed the McCarran Act in 1950, obliging all designated subversive organizations to register with the federal government and creating heavy penalties for leaders who refused to cooperate, the entire executive committee of the VALB resigned in 1950. In its place, two Lincoln veterans stepped forward: Milton Wolff became the National Commander; Moe Fishman became the Executive Secretary/Treasurer and served the organization in an executive capacity for the rest of his life. Fishman and Wolff led the VALB defense before the Subversive Activities Control Board in 1954. After their efforts failed, they pursued the appeals process that led to a court ruling in their favor in the 1970s, denying the constitutionality of the Attorney General’s list and the SACB’s rulings. Through it all, Fishman reminded the vets, “we have not forgotten that our main purpose in life is our anti-Franco activity.” “The long fight is over,” he wrote soon afterward to vet Herman “Gabby” Rosenstein, “and we are in (so to speak) [as] a legitimate non-subversive organization. I’m not sure that is good. Maybe we better do something subversive and get back on it otherwise the public we are trying to reach, especially the youth constituency, will look askance at these ‘revisionists’ who have stopped being subversive and have a U.S. Court of Appeals that agrees we are not. How about that?” During the dark years of the blacklists, Fishman kept the VALB organization running, producing short 4-page issues of The Volunteer to keep the vets apprised of various Cold War political cases, providing information for individual defense trials, and participating in protest demonstrations against Spanish government policies and cultural activities in the United States. These were times when he felt like a one-man band. “I’m the organization,” he said with little exaggeration for a 1962 article that appeared in Esquire. “If there’s something to decide, I talk it over with the guys and then decide what I’m going to do. Cockeyed, but that’s the way it is.” Five years earlier, the two VALB leaders, Moe and Milt, faced an empty treasury and considered disbanding the organization. They decided to poll some of the vets, who resoundingly opposed the idea. Meanwhile, Moe had received a letter from a Spaniard who had worked with the VALB in New York in the 1940s and was now in a Franco prison. He responded by summoning a campaign to aid all political prisoners of Spain. An aid and amnesty project became VALB’s major focus until the dictator died in his bed in 1975. Moreover, to raise funds for the prisoners and their families, the reconstituted VALB held its first reunion in a decade in 1957, a ceremonial gathering that continues now under the auspices of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives. As veterans reached retirement age and returned to the VALB in the 1970s, Fishman remained a constant in the organization’s activities. He participated in innumerable panels and conferences, spoke to students in high schools and colleges around the country, and traveled to international meetings about the Spanish Civil War. In his public presence, he revealed an incredible memory for names and historical details. He also knew all the ghosts in the closet, though he often refused to reveal anything that he had learned confidentially. He had the patience to listen to the most oft-asked, often hostile questions and yet offer clearly recited answers. He seldom allowed a speaker to escape a comment with which he disagreed. Indeed, he seemed sometimes a relentless questioner, assuring that the role of the Lincoln volunteers received its proper due. For years, seemingly forever, Moe Fishman stood at the center of a halo that surrounded the Americans who fought in the Spanish Civil War. He relished the spotlight. Lean, well-dressed in suit and tie, dark eyebrows and brown mustache offset by a full gray head, he carried the vitality of a young man’s cause into his old age. Each year at the annual reunion, it was his voice that announced recent deaths and called the roll of the surviving veterans in attendance. His silence brings the end of an era. - Peter N. Carroll

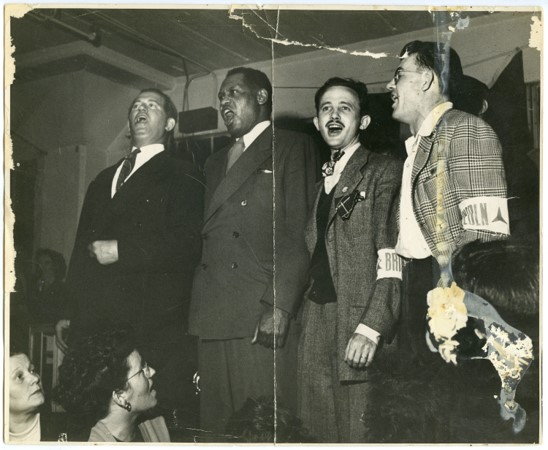

Photographs: Bart Van der Schilling, Paul Robeson, Moe Fishman and Arthur Landis, sing during a VALB reunion, ALBA Photo66, Box 1, Folder 3; and three additional photographs of Moe Fishman, undated.; Two photographs of Moe Fishman, by Richard Bermack.